PLEASE DON’T FEED THE FISHIES

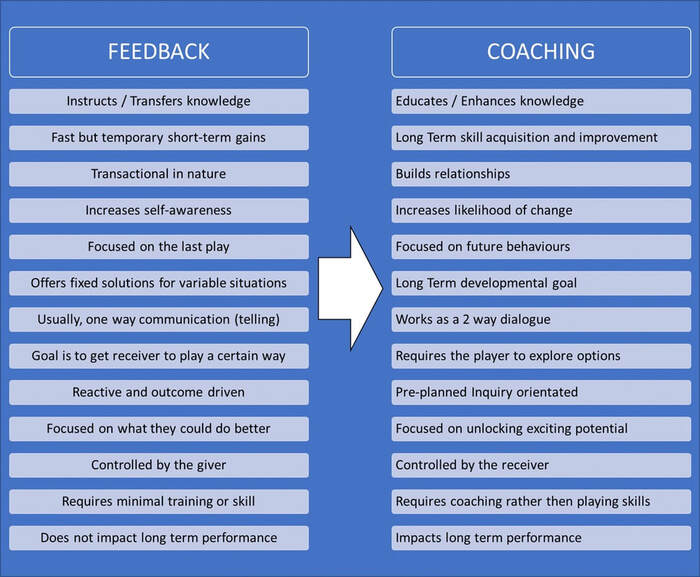

Feedback is a great way to increase someone’s self-awareness, particularly of one’s strengths and weaknesses. However, to expect meaningful changes to occur simply from the process of feedback without providing additional assistance and the right environment is naïve at best.

In underwater hockey rookies rarely get structured development time and this leads to a situation where they are often hungry for knowledge and appreciative of any delivery method. We have developed a culture where telling a newer player what they could do to improve during a game is both normal and accepted. Unfortunately it also has some less than desirable outcomes.

Feedback shuts down a player's mental dashboard. The player understands that they did something wrong and needs to re-focus.

Depending on their emotional control (which nobody knows) they may feel slightly defensive (which increases stress) or even happy (which narrows their focus to the casually offered feedback). Regardless the emotional outcome, the result is lowered creativity and decreased executive functioning. Effectively you have taken away the players need to think!

Feedback is almost always backwards looking, usually based on the last play. It involves involves telling the rookie what they should have done during any convenient break in the game. The giver is now asking the new player to stop what they are working on or thinking about and focus, not only on the last play, but on a specific aspect of that play.

The experienced player has just watched the rookie make multiple moves while holding their breath in a stressful environment and discounts the 15 successfully executed actions and decides to point out the one move that (in their opinion and from their perspective) the player could do better. It does not matter how you deliver that information...it is generally received as a marginal or needing to be better grade.

Each developing player has diverse and individualized learning objectives and unless the person offering feedback is aware of those, they replace a developed learning plan with whatever knowledge or tactical opinion they have. Specifically, if you tell a new player that they should hold their stick in a certain way to improve their ability to keep the puck, it may be great feedback, but it replaces the short & long-term objectives of the rookie. It also internalizes the player's focus away from team play.

Continual, even well-meaning feedback, from multiple people that you do not have a relationship with is, at the least, confusing and when repeated weekly is fatally discouraging. In fact, when people hear the phrase “Do you mind if I give you some feedback?” they assume they are about to hear something negative. Even if the player has asked for some ‘in-game’ feedback, it invariably leads to the player being discouraged and lowers their commitment, and more importantly their enjoyment, to the event and the sport.

The negative impact of feedback is compounded in underwater hockey because of a lack of trained coaches and few planned coaching environments. The unfortunate reality is that many players believe there is a connection between their skill level, experience or understanding of the game, and their ability to give unsolicited feedback. The usual defence of these efforts is “well that’s how I learned” or “how else will they learn”. It becomes even more complicated because the person offering feedback believes they are adding value, and then enjoys the satisfied feeling of being valued.

One of the fundamental misunderstandings in UWH is the difference between a game and a practice. In a game the objective is to minimize player mistakes and capitalize on the opposing teams' mistakes. In a practice the objective is to maximize mistakes to create learning opportunities. Because we have very few designated practice environments, we attempt to teach players during our regular games. It can be done, but only by allowing players to make mistakes in games without offering immediate feedback.

We are lucky to have practices and games and I would be delighted if the more experienced players (who like offering feedback) would give back to our practices as well (we always need the help). Or if you see something that could be an area of improvement for a player let me know or even let them know after the game or over a beer but please not during the game. Most of the new players love talking to experienced players and you (as the experienced player) need to also want to use some of your valuable time to share your wisdom.

Unsolicited feedback and not understanding coaching are the biggest barriers to retention of rookies.

The ones that do survive the current culture, which is essentially ritual hazing, find it difficult to develop beyond a perennial B player level.

In underwater hockey rookies rarely get structured development time and this leads to a situation where they are often hungry for knowledge and appreciative of any delivery method. We have developed a culture where telling a newer player what they could do to improve during a game is both normal and accepted. Unfortunately it also has some less than desirable outcomes.

Feedback shuts down a player's mental dashboard. The player understands that they did something wrong and needs to re-focus.

Depending on their emotional control (which nobody knows) they may feel slightly defensive (which increases stress) or even happy (which narrows their focus to the casually offered feedback). Regardless the emotional outcome, the result is lowered creativity and decreased executive functioning. Effectively you have taken away the players need to think!

Feedback is almost always backwards looking, usually based on the last play. It involves involves telling the rookie what they should have done during any convenient break in the game. The giver is now asking the new player to stop what they are working on or thinking about and focus, not only on the last play, but on a specific aspect of that play.

The experienced player has just watched the rookie make multiple moves while holding their breath in a stressful environment and discounts the 15 successfully executed actions and decides to point out the one move that (in their opinion and from their perspective) the player could do better. It does not matter how you deliver that information...it is generally received as a marginal or needing to be better grade.

Each developing player has diverse and individualized learning objectives and unless the person offering feedback is aware of those, they replace a developed learning plan with whatever knowledge or tactical opinion they have. Specifically, if you tell a new player that they should hold their stick in a certain way to improve their ability to keep the puck, it may be great feedback, but it replaces the short & long-term objectives of the rookie. It also internalizes the player's focus away from team play.

Continual, even well-meaning feedback, from multiple people that you do not have a relationship with is, at the least, confusing and when repeated weekly is fatally discouraging. In fact, when people hear the phrase “Do you mind if I give you some feedback?” they assume they are about to hear something negative. Even if the player has asked for some ‘in-game’ feedback, it invariably leads to the player being discouraged and lowers their commitment, and more importantly their enjoyment, to the event and the sport.

The negative impact of feedback is compounded in underwater hockey because of a lack of trained coaches and few planned coaching environments. The unfortunate reality is that many players believe there is a connection between their skill level, experience or understanding of the game, and their ability to give unsolicited feedback. The usual defence of these efforts is “well that’s how I learned” or “how else will they learn”. It becomes even more complicated because the person offering feedback believes they are adding value, and then enjoys the satisfied feeling of being valued.

One of the fundamental misunderstandings in UWH is the difference between a game and a practice. In a game the objective is to minimize player mistakes and capitalize on the opposing teams' mistakes. In a practice the objective is to maximize mistakes to create learning opportunities. Because we have very few designated practice environments, we attempt to teach players during our regular games. It can be done, but only by allowing players to make mistakes in games without offering immediate feedback.

We are lucky to have practices and games and I would be delighted if the more experienced players (who like offering feedback) would give back to our practices as well (we always need the help). Or if you see something that could be an area of improvement for a player let me know or even let them know after the game or over a beer but please not during the game. Most of the new players love talking to experienced players and you (as the experienced player) need to also want to use some of your valuable time to share your wisdom.

Unsolicited feedback and not understanding coaching are the biggest barriers to retention of rookies.

The ones that do survive the current culture, which is essentially ritual hazing, find it difficult to develop beyond a perennial B player level.